35c3 junior ctf writeups part 1

It’s a new year and that means there has been another Chaos Communication Congress organized by the Chaos Computer Club.

It is becoming a tradition for our team over at HackThisSite to take part in the junior ctf that takes place during the congress. Last year we dropped from first to second in the very last minute, this year we finished 7th.

This is the first of two writeups I’ll make for this CTF. This writeup and others can also be found in our CTF writeup repo.

Challenge 1: DANCEd

DANCEd was the least solved crypto challenge, and the first challenge I took.

It describes a simple application writen in Go to register for a dance class. It had 2 main functions:

- it encrypts your dance class registration (choice of class + your name) and gives you the encrypted value to use as a token as proof that you registered for the class

- and it lets you see all other registrations in encrypted form (which is obviously where the flag is hidden). Additionally it could output some static help text and had a debug function that output the source code of the running application.

Since I never used Go I also wanted to know how easy the language would be. Go is known for being “safe” and people are less likely to make mistakes compared to C/C++, which made me pretty confident the problem wasn’t going to be in any obscure syntax error. So while I did lookup the documentation for some specific Go libraries and functions I would attempt to deduce its syntax only based on the provided code.

Despite not having a single comment, I think the code was very clear and it was easy to see what was going on. In broad strokes:

- theres a listener listening to connections

- runs some function on connection to give user some options

- runs some other functions depending on the selected options

Super standard stuff, it didn’t require a million 3rd party libraries (node.js) or 20 classes to do it properly (java).

Identification

by WhiteTimberwolf

Image license: Public Domain

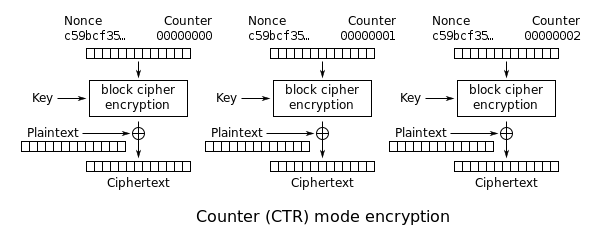

We’re interested in the user registration part of this code. It is taking the class name and username concatenated together and encrypting the result. To encrypt, it is generating a unique keystream for each message and XORing that with the plaintext message.

If all that sounds familiar, thats because it is the basic working principle of a block cipher in counter mode. Useful for turning a block cipher into a stream cipher.

Understanding the keystream

So far we haven’t actually identified the problem with this implementation yet. There are 3 parameters in final encryption step: the keystream, the message and the resulting encrypted message. Using some basic boolean arithmetic we know we can get any of those 3 variables as long as we have the other 2.

We are able to extract the key stream/block key used for our own messages but it is unique to our message so we can’t use it to decrypt anything else. It is time to take a closer look at what this keystream actually contains.

func generateKeyStream(count uint32) []byte {

key := [8]uint32{0xffffffff, 0xffffffff, 0xffffffff, 0xffffffff, 0xffffffff, 0xffffffff, 0xffffffff, 0xffffffff}

block := [4][4]uint32{

{0x61707865, key[0], key[1], key[2]},

{key[3], 0x3320646e, nonce[0], nonce[1]},

{count, 0x00000000, 0x79622d32, key[4]},

{key[5], key[6], key[7], 0x6b206574}}

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

doubleRound(&block)

}

for c := 0; c < 4; c++ {

for r := 0; r < 4; r++ {

fmt.Printf("%08x ", block[c][r]);

}

fmt.Printf("\n");

}

var stream []byte

current := make([]byte, 4)

for c := 0; c < 4; c++ {

for r := 0; r < 4; r++ {

binary.LittleEndian.PutUint32(current, block[c][r])

stream = append(stream, current...)

}

}

return stream

}It starts off with a block (a 4 by 4 array of unsigned integers) that contains the key, two nonce’s and a counter. It preforms some operation on this block 10 times and then turns it into a sequential stream of numbers.

Looking at the simple wikipedia intro on counter mode would give you some hints on how this is supposed to work. I picked 2 statements I thought were most relevant to this challenge.

-

The counter can be any function which produces a sequence which is guaranteed not to repeat for a long time, although an actual increment-by-one counter is the simplest and most popular.

-

The usage of a simple deterministic input function used to be controversial; critics argued that “deliberately exposing a cryptosystem to a known systematic input represents an unnecessary risk.”

However, today CTR mode is widely accepted and any problems are considered a weakness of the underlying block cipher, which is expected to be secure regardless of systemic bias in its input.

Now we let’s look at that code keeping those 2 things in mind.

inputs

The key in this case is known (all 0xFF’s), which is a bit silly but not a flaw on its own (point 2).

The next value of interest is the counter. This is the important bit that makes sure that each keystream is only ever used once (different for each user) and is what turns it into a stream instead of just a block cipher (point 1). Each encrypted message relies on the existence of the previous message, in this case on how many messages not the content of those previous messages. We can retrieve a list of all encrypted messages, so we know this value for our own message, and for any other encrypted message.

The two nonce’s (number only used once) were generated when the program first ran and stored in nonce.txt. To generate them it used the rand.Read() function from the crypto.rand package. Its documentation tells us the following:

Package rand implements a cryptographically secure random number generator.

Since Go was created to avoid dumb programming mistakes, I have no reason to doubt this documentation and it is safe to assume we won’t be able to predict these numbers.

The only unknown input remaining is the nonce values. Even though a lot of inputs are known or easily retrieved, not all of them are so we still can’t reverse the encryption. We’ll need to look at the underlying block cipher to find a flaw (point 2).

The flaw

The function that can be considered the underlying block cipher of this implementation is called doubleRound():

func doubleRound(block *[4][4]uint32){

for i := 0; i < 4; i++ {

block[(1 + i) % 4][i] = block[(1 + i) % 4][i] ^ bits.RotateLeft32(block[(0 + i) % 4][i] + block[(3 + i) % 4][i], 7)

block[(2 + i) % 4][i] = block[(2 + i) % 4][i] ^ bits.RotateLeft32(block[(1 + i) % 4][i] + block[(0 + i) % 4][i], 9)

block[(3 + i) % 4][i] = block[(3 + i) % 4][i] ^ bits.RotateLeft32(block[(2 + i) % 4][i] + block[(1 + i) % 4][i], 13)

block[(0 + i) % 4][i] = block[(0 + i) % 4][i] ^ bits.RotateLeft32(block[(3 + i) % 4][i] + block[(2 + i) % 4][i], 18)

}

for i := 0; i < 4; i++ {

block[i][(1 + i) % 4] = block[i][(1 + i) % 4] ^ bits.RotateLeft32(block[i][(0 + i) % 4] + block[i][(3 + i) % 4], 7)

block[i][(2 + i) % 4] = block[i][(2 + i) % 4] ^ bits.RotateLeft32(block[i][(1 + i) % 4] + block[i][(0 + i) % 4], 9)

block[i][(3 + i) % 4] = block[i][(3 + i) % 4] ^ bits.RotateLeft32(block[i][(2 + i) % 4] + block[i][(1 + i) % 4], 13)

block[i][(0 + i) % 4] = block[i][(0 + i) % 4] ^ bits.RotateLeft32(block[i][(3 + i) % 4] + block[i][(2 + i) % 4], 18)

}

}This should be secure.. but we’ll find it isn’t.

When I first thought the flaw was in here I simply misread the code.

block[i][(1 + i) % 4]

block[(1 + i) % 4][i]

Those two lines look very similar, but they are in fact very different. I thought it was only doing it with columns and thus the nonce part in our 4x4array wasn’t influenced by the counter part, so if I could extract my own keystream those columns would remain the same I’d have the (modified) nonce values.

Clearly that isn’t the case.

The actual flaw is equally(or more?) simple. And goes back to the stuff we said about XOR earlier.

If you know 2 parameters, you can find the 3rd by simply XORing again. The 3 values are the initial value in the array, the value it gets XORed with, and the new value at that same position in the array. So to reverse it we simply need to do the same operation as done in this function, but in reverse order.

We now have enough information to decrypt any message:

- We can extract the keystream used on our own message by XORing our plaintext message with the encrypted value

- We can reverse the keystream back into its original values by doing the same operations in reverse order

- We can use the same values to generate the correct (counter dependent) keystreams used for all the other messages

- We can use the correct (counter dependent) keystreams to decrypt the encrypted messages

Let’s get to it!

Performing the attack

Extract our keystream and reverse it

To make extracting the keystream easy and stay with the language used in the challenge I made some helper function in the original app to calculate it and added an entry for users to select it in the handleConnection() function.

func doubleunRound(block *[4][4]uint32){

for i := 3; i >= 0; i-- {

block[i][(0 + i) % 4] = block[i][(0 + i) % 4] ^ bits.RotateLeft32(block[i][(3 + i) % 4] + block[i][(2 + i) % 4], 18)

block[i][(3 + i) % 4] = block[i][(3 + i) % 4] ^ bits.RotateLeft32(block[i][(2 + i) % 4] + block[i][(1 + i) % 4], 13)

block[i][(2 + i) % 4] = block[i][(2 + i) % 4] ^ bits.RotateLeft32(block[i][(1 + i) % 4] + block[i][(0 + i) % 4], 9)

block[i][(1 + i) % 4] = block[i][(1 + i) % 4] ^ bits.RotateLeft32(block[i][(0 + i) % 4] + block[i][(3 + i) % 4], 7)

}

for i := 3; i >= 0; i-- {

block[(0 + i) % 4][i] = block[(0 + i) % 4][i] ^ bits.RotateLeft32(block[(3 + i) % 4][i] + block[(2 + i) % 4][i], 18)

block[(3 + i) % 4][i] = block[(3 + i) % 4][i] ^ bits.RotateLeft32(block[(2 + i) % 4][i] + block[(1 + i) % 4][i], 13)

block[(2 + i) % 4][i] = block[(2 + i) % 4][i] ^ bits.RotateLeft32(block[(1 + i) % 4][i] + block[(0 + i) % 4][i], 9)

block[(1 + i) % 4][i] = block[(1 + i) % 4][i] ^ bits.RotateLeft32(block[(0 + i) % 4][i] + block[(3 + i) % 4][i], 7)

}

}

func optTest(c net.Conn) {

c.Write([]byte("\n"))

c.Write([]byte("testing\n"))

bufMSG := make([]byte, 65)

c.Write([]byte("\n Enter the plain message: "))

bufReader := bufio.NewReader(c)

n, _ := bufReader.Read(bufMSG)

if n < 2 || n > 65 {

c.Write([]byte("\n Abort.\n"))

return

}

bufReader.Reset(c)

bufTOKEN := make([]byte, 65*2)

c.Write([]byte("\n Enter the token: "))

i, _ := bufReader.Read(bufTOKEN)

//token is twice as long since its a hex representation

if i < 2 || i > 129 {

c.Write([]byte("\n Abort.\n"))

return

}

bufRAW := make([]byte, 65)

j, _ := hex.Decode(bufRAW, bufTOKEN)

if j < 2 || j > 65 {

c.Write([]byte("\n Abort.\n"))

return

}

c.Write([]byte("converting back to bytes..\n"));

//extracting stream

strm := make([]byte, len(bufMSG))

for i := 0; i < len(bufMSG) && i < 64; i++ {

strm[i] = byte(bufMSG[i]) ^ bufRAW[i]

}

block := [4][4]uint32{

{0x61707865, 0xFF, 0xFF, 0xFF},

{0xFF, 0x3320646e, 0xFF, 0xFF},

{0xFF, 0x00000000, 0x79622d32, 0xFF},

{0xFF, 0xFF, 0xFF, 0x6b206574}}

tmp := make([]byte, 4)

i = 0

for c := 0; c < 4; c++ {

for r := 0; r < 4; r++ {

for h := 0; h < 4; h++ {

tmp[h] = strm[i]

i++

}

block[c][r] = binary.LittleEndian.Uint32(tmp)

}

}

fmt.Printf("Retrieved: \n");

for c := 0; c < 4; c++ {

for r := 0; r < 4; r++ {

fmt.Printf("%08x ", block[c][r]);

}

fmt.Printf("\n");

}

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

doubleunRound(&block)

}

fmt.Printf("Unrounded\n");

for c := 0; c < 4; c++ {

for r := 0; r < 4; r++ {

fmt.Printf("%08x ", block[c][r]);

}

fmt.Printf("\n");

}

}Most of it is just code to grab the input and convert it to and from its hex representation, the crutial part is: strm[i] = byte(bufMSG[i]) ^ bufRAW[i] and the doubleunRound() function (which is just the original doubleRound() function in reverse order)

We can now encrypt a value on the server and use its plaintext and encrypted value to retrieve the used nonce’s. We should just make sure that the plaintext we encrypt is as long as possible so we have enough data to work with (I just used the max allowed length of A’s).

The result would look something like this:

Retrieved:

0ee9d592 13e78d53 e204a8b4 d60c4316

a7f8887c f9ba1d3c 7de83594 e8111dc4

acf7014e 34535918 45dca61b 8b286e22

8d967978 549889b0 5980aa28 8545e99e

Unrounded

61707865 ffffffff ffffffff ffffffff

ffffffff 3320646e 8c3ec26e de0befac

0000043b 00000000 79622d32 ffffffff

ffffffff ffffffff ffffffff 6b206574

Looking back at where the nonce’s are stored, we now know that nonce[0] = 8c3ec26e and nonce[1] = de0befac

Decrypting it all

I needed to retrieve a list of all the encrypted values so I actually have something to decrypt. That was easy enough using this simple command (using the server’s ip instead of localhost):

nc 127.0.0.1 11520 | tee test.txt

This let me use the remote server as normal and record all its data to test.txt, a bit of cleanup later and we have a list of encrypted messages separated by a newline.

Similar to the previous step, I added some functionality to the original Go code. I also made sure to change the nonce.txt to have the newly acquired values.

func decrypt(msg string, count uint32) []byte {

stream := generateKeyStream(count)

cipher := make([]byte, len(msg))

tmp := make([]byte, len(msg)/2)

l, _ := hex.Decode(tmp, []byte(msg))

for i := 0; i < l && i < 64; i++ {

cipher[i] = tmp[i] ^ stream[i]

}

return cipher

}

func optHax(c net.Conn){

var count uint32

f, e := os.OpenFile("dump.txt", os.O_CREATE|os.O_APPEND|os.O_RDWR, 0644)

check(e)

scanner := bufio.NewScanner(f)

count = 0

tmp := make([]byte, 56*3)

c.Write([]byte("dumping"))

for scanner.Scan() {

c.Write([]byte("\nencrypted: "))

c.Write([]byte(scanner.Text()))

tmp = decrypt(scanner.Text(), count)

c.Write([]byte("\ndecrypted: "))

c.Write(tmp)

count++

}

}This code is pretty simple too, read a line from the list of encrypted messages, pass it to the decrypt() function. Then generate a keystream based on the count, convert the hex representation into bytes and XOR it with the keystream.

We run our added function and look for the flag in the results.

dumping

encrypted: 598049294de2a82413696291130af797a10174c62b4a2d1a76c9cc3e7340e03904f5c01d

decrypted: salsa 35C3_DJ_B3RNSTE1N_IN_TH3_H0USE

encrypted: ed0d65db765c7d5fd685274b036790006f

decrypted: tango Marty McFly

encrypted: 66e207d422f271ad0364815cc7fca9a6e40baa

decrypted: chacha Tony Holiday

encrypted: f3e5b924e199917456c243

decrypted: salsa dlabi

Conclusion

We all know it, but its worth repeating: don’t make up your own crypto if you don’t know exactly what you’re doing. Just use an existing audited 3rd party library.

The known key, lack of padding and availability of all messages are all bad.. but they didn’t fundamentally break this cipher.

It was the self made up block cipher part of this implementation that used reversible methods to generate the keystream that made it useless.

An other lesson was that Go seems simple enough, I should make something in it sometime for fun.